is when we trawl through the That’s archives for a work of dazzling genius written at some point in our past. We then republish it. On a Thursday.

“I love short hair. But when I had it, people thought I was a lesbian,” a Chinese acquaintance once told me. She gestured at her straight, shoulder-length locks.

“It’s called ‘mama’s hairstyle,’ after daughters who keep their hair long to please their mothers.”

Ironic, considering that her mother came of age in an era when short hair was not only normal but sometimes even mandated: during the Cultural Revolution of the ’60s and ’70s, long styles and perms were among the casualties of the fight against capitalist culture.

But short hair was trending well before then. As far back as Republican China (1912-1949), women have been chopping off their manes in the name of social, political and sexual liberation.

In a sense, adoption of short styles has both reflected and crystallized a century’s worth of struggle and change for Chinese women. Take a trip down history lane with us as we explore this hairy issue in depth.

New Women and Modern Girls

Trendy Shanghai women (1932, Shanghai Library Archives)

Trendy Shanghai women (1932, Shanghai Library Archives)

According to scholar Hung-Yok Ip, less than a decade after the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911, young female progressives began cutting their luscious locks, leaving behind the styling and ornaments of a now bygone era.

The so-called ‘new women’ accompanied the look with plain, sober clothing, symbolizing a novel outlook: That females too could contribute to China’s transformation into a modern nation.

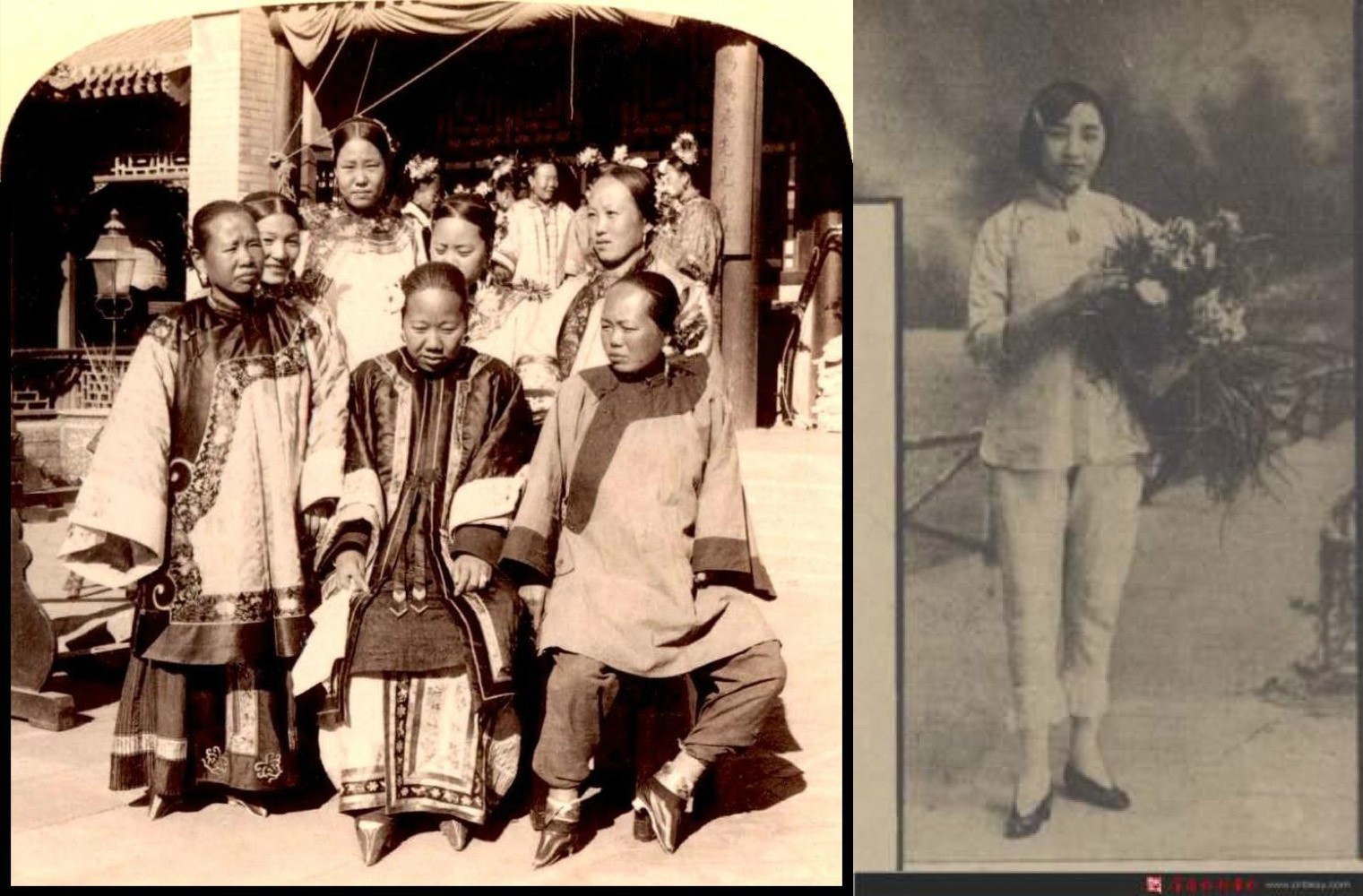

Pre-revolution household vs. a ‘new woman’ (1934, Shanghai Library Archives)

Pre-revolution household vs. a ‘new woman’ (1934, Shanghai Library Archives)

Although short-lived, the movement brought a kind of liberation – both physical and psychological – from staid traditions. As a young Mao Zedong put it in 1919, as cited by Hung-Yok Ip, “If a woman’s head and a man’s head are actually the same… why must women have their hair piled up in those ostentatious and awkward buns?”

Not long afterward, short hair for women gained even more traction, but for very different reasons: Bobs and glamorous fashions from a world away were winning over young women in China’s big cities.

The fashion-forward, worldly ‘modern girl’ of the early ’30s started flaunting short cuts, sometimes paired with one of the new cheongsams that were more form-fitting than ever before, according to scholar Antonia Finnane. It was liberation of another kind, and it had its detractors.

Images via the Shanghai Library Archives

Images via the Shanghai Library Archives

Cartoons made fun of ‘modern’ thigh-high hemlines and the sexual openness they seemed to represent. The ambiguity of the new look made its way into other popular media too. In the classic 1934 film The Goddess, actress Ruan Lingyu plays a single mother who’s both powerful and powerless. Her fashionable appearance – short perm and colorful cheongsam – allows her to attract customers as a sex worker, but they also put her at risk of mockery and exploitation.

A still from The Goddess (1934)

A still from The Goddess (1934)

Despite the drawbacks, the popularity of modern fashions persisted, as some Western observers noted. As late as 1941, a photograph from the International Mission Photography Archive of the Yale Divinity Library was accompanied by this caption: “A year or so ago when ‘shingled’ hair was the fashion all Chinese girls had short hair although it did not really suit their particular style of features.”

The writer notes with relief that long hair is once again in vogue, and that “In these days [Chinese women’s] style of hair dressing is as varied as in any other country.”

Liberation Chic

Just over two decades later, though, long locks were taboo.

According to China Daily, byy the ’50s, extra-short ‘liberation’ bobs had begun making waves among women of the new People’s Republic of China. But the foundation for the fashion was set even before the Communists’ 1949 takeover.

In the early ’30s, as quoted by Hung-Yok Ip, a soldier told new female recruit Lu Guixiu: “Bobbed hair is convenient and sanitary. It is easy to take care of when you are wounded.” Despite reservations, she and other peasant soldiers adopted the new look for its practicality.

The less-is-more mentality also pervaded the Long March, which reduced Communist forces to a fraction of their original size. According to Ip, the book The Heroines in the Long March recounts that in the urgency of their flight female soldiers “used their fingers to ‘tidy’ their hair every morning,” having “neither comb nor mirror.”

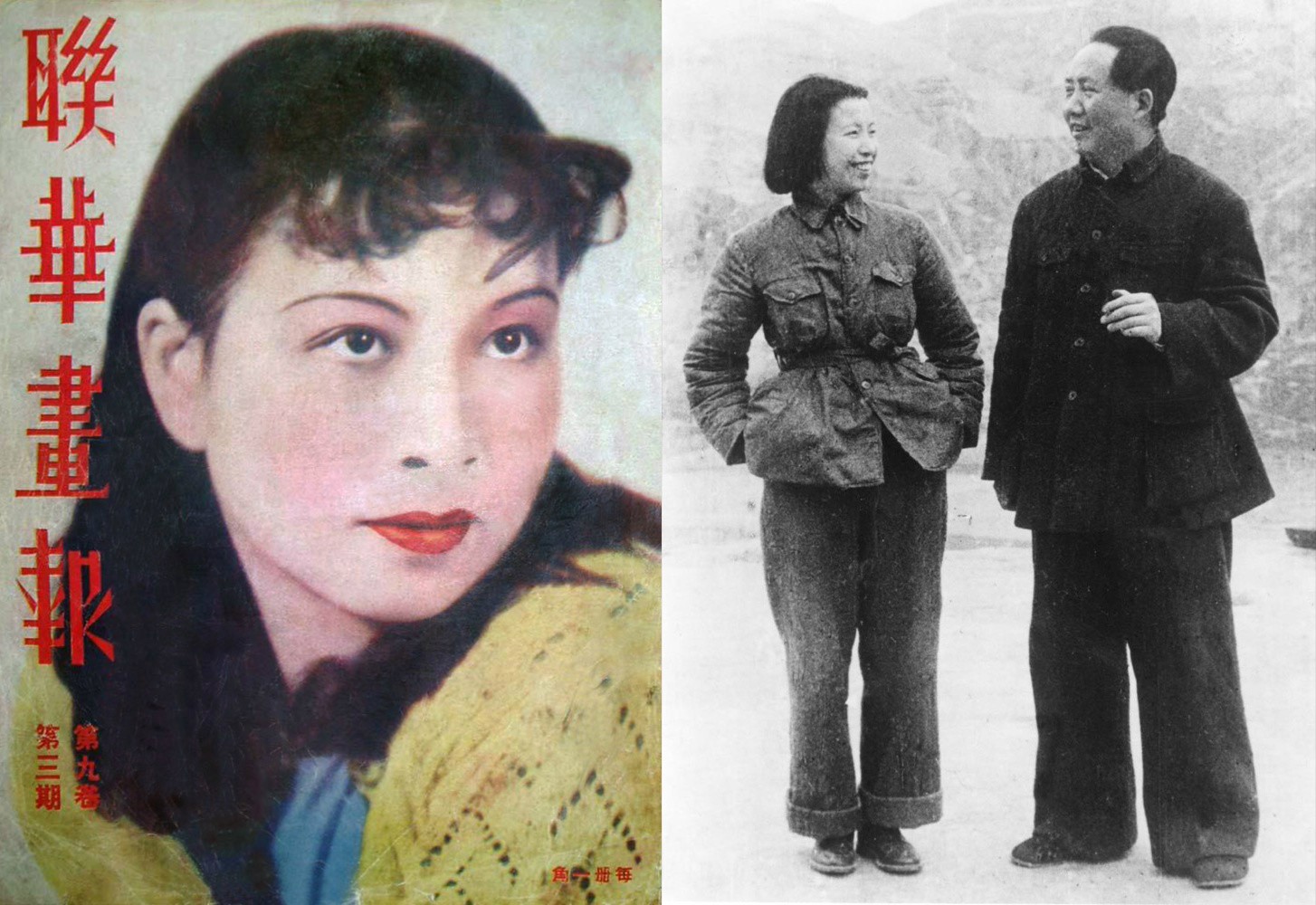

Even after the army made it to the refuge of Yan’an, the survivalist-chic look persisted. A ’30s photo shows a young Mao with his fourth wife Jiang Qing, both in military-style garb and haircuts of similar length. Although her uniform shirt is cinched at the waist, it’s still a far cry from the former actress’ carefully-styled appearance on the cover of a movie magazine earlier that decade.

Jiang Qing before and after

Jiang Qing before and after

A decade into Communist rule, as Antonia Finnane explains it, even Song Ching-ling – Sun Yat-sen’s widow and Vice Chairperson of the Standing Committee of the People’s Congress – had turned in her habitual plain qipao for shirts and pants, a sign of the changing times.

But unlike with the ‘new women’ of decades before, Communist women’s androgynous style was accompanied by significant political progress: the landmark Marriage Law of 1950 required both parties’ consent, cracking down on arranged unions, bigamy and human trafficking. It also raised the marriage age for females and males to 18 and 20, respectively, and affirmed a woman’s right to divorce.

Women found their way into the working world as well, although they often had to balance jobs with household chores, as John Bauer and other researchers discovered. In their article on gender issues in China, the team cites surveys in Nanjing that show that before 1949, close to 71% of women had no employment. Of those married between 1950-65, however, 70.6% worked, and over 90% of women wedded in the following decade also found jobs.

Cutoff Point

It’s a testament to the power of the perm that only major social upheaval could cut off its popularity.

But the doom of heat-induced curls – and too-long hair, and excessive accessories – eventually arrived with a vengeance during the Cultural Revolution.

Before 1966, permed waves and hair ribbons weren’t uncommon, Ip states, even among progressive women. Afterwards, however, even medium-length hair risked criticism and rectification at the hands of scissors-wielding Red Guards.

At the beginning of his brief essay ‘Cultural Revolution and Hair,’ scholar Gu Nong brings up an anecdote by writer Yang Jiang in which she recalls having half her hair cut off in ‘yin yang’ style during a criticism.

Gu, a former Red Guard himself, recalls an ‘unspoken rule’ of the period: ‘one braid is feudalist, two is capitalist, shoulder-length hair is revisionist and all must be swept away.’

By contrast, the pinnacle of revolutionary beauty might be found in The Red Detachment of Women, one of the Eight Model Operas (conceived by Jiang Qing, incidentally) that dominated Chinese entertainment for a decade.

From a 1972 production of Red Detachment of Women

From a 1972 production of Red Detachment of Women

The ballet-slash-opera, which features female dancers en pointe wielding rifles, tells the story of peasant woman Wu Qinghua. Wu escapes a tyrannous landlord and learns to become a valuable member of an all-female company in the Red Army – a troop of uniform-clad women, all of whom sport short hair.

New Growth

Not long after China’s reform and opening up in 1978, newly receptive Chinese women began adopting hairstyles from around the world. Style influences ranged from ‘disco queen’ Zhang Qiang, who favored a daring afro, to Hong Kong actress Maggie Cheung’s sideways ponytail.

Short hair lost much of its cachet although the odd celebrity, such as pop star Li Yuchun, continues to champion close-cropped cuts.

Li Yuchun in 2015

Li Yuchun in 2015

Still, in first-tier cities like Shenzhen or Guangzhou, it’s not hard to spot women with shorter cuts among a throng of curls, waves, iron-straightened locks and various dye jobs.

Huang Bingjie is one of them. A year ago, friends and family greeted her decision to chop it all off with surprise, although they’ve since gotten used to it.

Huang likes it too, saying she’ll most likely keep her ‘cool’ cut for another two or three years before switching it up.

Huang Bingjie (left) and Wendy Zhao (right), 2018

Huang Bingjie (left) and Wendy Zhao (right), 2018

Wendy Zhao, 30, is another close-crop adoptee, although she’s since changed her mind and concealed her hair under a wig during the awkward growing-out phase.

“A lot of girls want to cut [their hair short]… but they won’t do it if they think it won’t suit them.”

Zhao is both fascinated and repulsed by another bold style choice: Shaving one’s head. She says she won’t do it, then admits to being curious anyway: “I just don’t know what being bald would feel like. It would be a new experience.”

Possibly even liberating.

This article was originally published in June 2018.

To see more Throwback Thursday posts, .

Almost all photos courtesy of Shanghai Library Archives and public domain. Journal articles cited above were accessed through JSTOR; see individual links for details.

![[Drink It]: In Defense Of Chinese Booze](https://www.life-china.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/1560839810-440x264.jpg)

Recent Comments