You know what they say, ‘Happy wife, happy life’ – but what happens when a marriage goes sour? When bickering turns into heated arguments? Or issues arise with infidelity or finances? When both people are past their limit, divorce is often the answer.

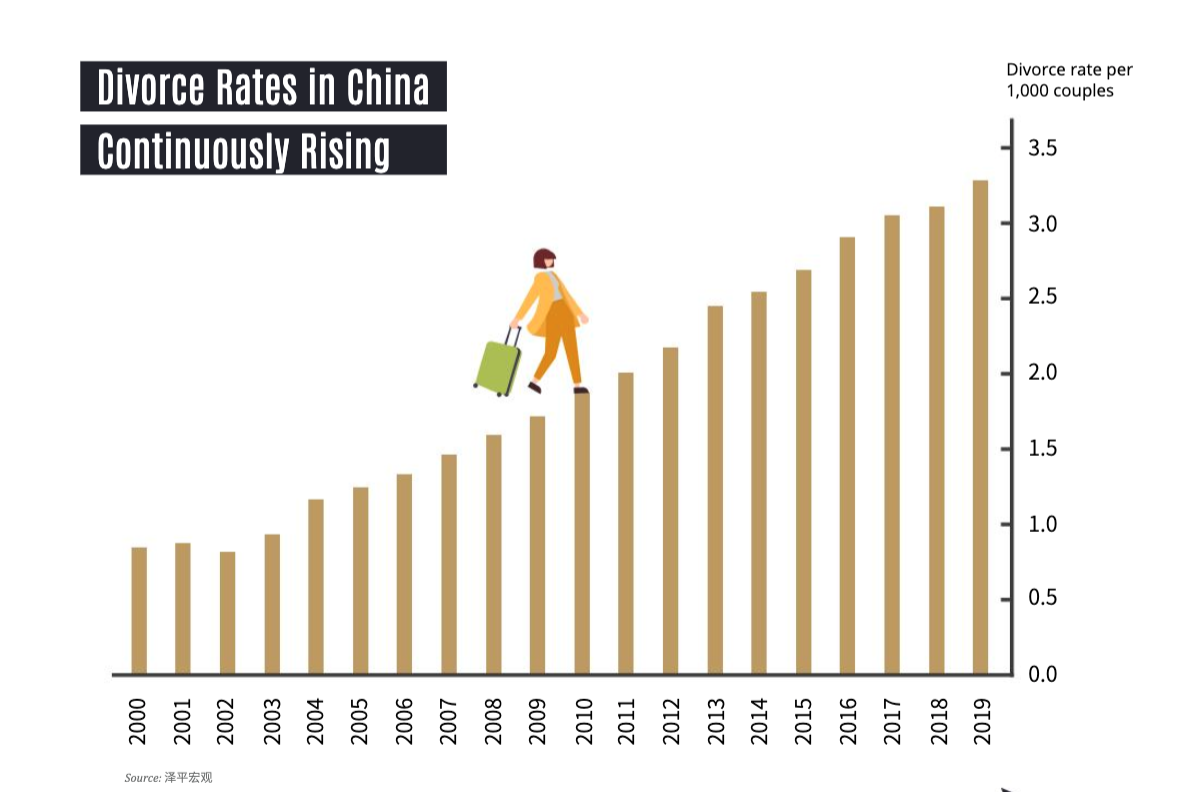

It has been well-reported that the overall divorce rate in China has been rising for the past two decades – and fast. China’s young married couples are untying the knot while others hope to ‘save the date’ for a later stage in life or avoid it entirely. Various factors can be attributed to the influx in divorcees such as the rise of social stability for women, communication breakdowns, changing thoughts on romance and the lack of intimacy education.

In the following, we address how society in China is shifting the perception of marriage and what’s being done to help couples stay committed through thick and thin.

Newlyweds

Many modern marriage customs in China can be traced back to the Zhou Dynasty (1046 BCE-256 BCE). As one may presume, though, marrying for love was not the goal in feudal society.

Marriage was mainly seen as a union and strategic alliance between two families to ultimately continue the ancestral line. In comparison, marriage today is a mishmash of factors like emotions, culture and sex to bond husband and wife.

These added elements make marriage both complex and fragile. When marriage quality fails to meet a partner’s expectations, they are often less afraid to give up on the relationship and live independently.

We reached out to Dr. Sharon Kong, a Shenzhen-based marriage consultant, who is well-known for her work in psychological counseling and has appeared on various South China television programs.

She tells us that the main reason behind China’s budding divorce rate is the rise of women’s power. Over the years, an increasing number of Chinese women have received higher education, growing their income and independence.

According to tradition, women were educated to uphold ‘Three Obediences and Four Virtues,’ which are ancient moral codes for single and married women. The Three Obediences are as follows: a woman is to obey her father before marriage, obey her husband once married and, after the husband dies, obey her son. All these principles implied that women existed for men.

Modern education shifts the focus inward, concentrating on women’s self-esteem and self-reliance. Statistically, it has been found that girls perform better than their male counterparts in both mental maturity and academic performance. China’s National Bureau of Statistics released a 10-year report in 2020 which found that over half of college graduates were female (50.6%) – a decade earlier that figure was 47.9%.

Education is the main driver helping women to narrow the pay gap, allowing for more independence. Especially in first-tier cities like Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen, women are allowed to flourish and show the full extent of their capabilities in the workforce.

Dr. Kong notes, “The phenomenon of overshadowing men is very common. Sometimes in a family, the woman is more decisive and assertive.”

While female empowerment is becoming more prevalent across industries in China, perhaps nowhere is it more visible in the public eye than the entertainment industry.

On May 20 (known as China’s unofficial Valentine’s Day), Xinjiang native Tong Liya, one of China’s most popular actresses, announced her divorce from actor and director Chen Sicheng.

Both Tong and Chen posted separate announcements on the Chinese social media platform Weibo, with Tong saying that she is “looking forward to the future.”

The 36-year-old actress had met Chen while filming the TV series Beijing Love Story around 2012, and they married two years later. Chen’s alleged affairs had plagued the relationship for several years, which ultimately led to public praise upon hearing news of the divorce. The positive perception of Tong’s divorce seems to be a defiant shift from past norms.

Changing ideologies of romance throughout generations have also affected the divorce rate. A 2017 sociology study by Yu Zhang summarized that Chinese women’s ideas on ‘romantic love’ are primarily influenced by the generation they lived in.

These different beliefs and values surrounding love coincide with the increasing divorce rate over the past two decades.

The 2021 China Marriage Report reveals that the average age of marriage in the nation is currently around 25 to 29 years old. This is a significant shift from what used to be the norm of 20 to 24 years old decades earlier. It also reflects a global trend of waiting longer before marrying.

The current majority who are getting married were born in the ’90s and have a very different understanding of sex and intimacy than Chinese women who were born in the ’50s.

In the ’50s, an intimate relationship was considered one between parent and child, where sexual love was an afterthought. Upholding a family was the most important matter: “When asked if they had ever thought of a divorce, their responses were ‘then what about my kids,’” Yu notes in her study. Even when husbands were caught cheating, marriage was kept at all costs. Due to family pressure and social expectations, married women in this generation had little recourse. More women may have left their husbands if they had more freedom to do so.

Those born in the ’70s lived during the economic reform and opening-up of China. A time of optimism, these women “hoped for a love and marriage,” or amatonormativity.

Amatonormativity is a term coined by philosophy professor Elizabeth Brake to describe the “widespread assumption that everyone is better off in an exclusive, romantic, long-term coupled relationship.” Divorce to these married women is often seen as a failure, even when family violence is present.

As for the ’90s babies, they grew up in a time of globalization. These women are independent and more self-aware, making divorce a logical option in the case of an unfulfilling marriage.

As generations pass, the notion of ‘romantic love’ changes and the attitudes towards marriage and divorce change as well.

However, the ideals of previous generations can still impact the choices of the next. Zhao Xia of Hubei province got married in 2018. At the time, she felt confident in her relationship but pressured to get married quickly. She acknowledges that her partner wasn’t quite ready.

“I wasn’t thinking about money, family or background. I thought I loved him and he loved me,” she told That’s. “But also, I was under pressure because […] my family were pushing me so much. They said, “You are old enough. If you don’t get married, it will be too late for you, and you’ll miss your chance to have a baby. If you don’t get married, we will introduce somebody to you, and we will decide when you get married.” So, at that time, I just registered [to get married].” Zhao got divorced from her husband after two years of marriage.

She adds, “one month after I got divorced, they wanted me to meet another guy and get married again. […] They didn’t care how I felt. I was hurt and maybe I didn’t want to get married anymore, but they didn’t ask.”

Another factor is the lack of intimacy education in China. In current society, resources on how to love and manage marriage are not always readily available. There is an insufficient amount of premarital education, and, as a result, the changes in identity and roles after marriage are not identified. Many enter a marriage without any form of training on how to be a husband, wife, or parent.

Dr. Kong shares, “Marriage is a matter of learning. Young people who have not studied accordingly will encounter many obstacles in marriage as they don’t know how to communicate with each other, and they don’t even have the consciousness to hire a professional marriage counselor.”

While Chinese parents are quick to seek out the best coaches and teachers for their children’s success, the notion of seeking someone qualified to help improve their marriage is not commonplace.

“They turn to their friends or parents whose suggestions are always subjective and unprofessional, which leads to conflicts between the couple not being dealt with in a timely manner. At this time, it is very easy for another person to wreck the relationship or give a long-term silent treatment [to their partner], which eventually leads to divorce,” she adds, noting that these incidents are more common than we think.

“The internal reason is that two people don’t understand how to get along closely. Even if they marry another person in the future, they are very likely to divorce again because they know nothing about being a husband or being a wife.”

In March 2021, a Chinese legislator also suggested premarital training sessions for couples before they decide to officially wed. Chen Aizhu, a deputy from the National People’s Congress, explained the training could “help to improve people’s sense of responsibility to the family, encouraging the new couples to be loyal in marriage and cherish their family.” From a professional and legislative viewpoint, this could provide a solution for couples planning to get married. But how about married couples already considering a divorce?

Inconvenient Truth

We spoke to Silvia, a 38-year-old local Guangzhou resident who gave us insight into how divorce is perceived in China. Agreeing to talk with us without using her full name, Silvia says she currently has friends who are in the process of getting a divorce.

She notes that the discussion around divorce is still largely taboo in Chinese culture despite the growing number of divorcees. Silvia believes divorce is less commonly discussed due to pride and privacy.

Gao Meilin, a Beijing-based photographer, managed to push past the challenging topic and gain a unique perspective of divorced couples around the Middle Kingdom.

“After talking with over 100 divorced couples, 12 agreed to let me take souvenir photos for them,” Gao says. She started capturing photos of divorced couples in 2019 for her graduation project at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, a project that lasted two years.

Her parents had divorced when she was young and, like presumably many other children, had to pretend her parents were still together when friends visited her home.

Gao also included her parents in the project, where she also asked each couple to write a secret note to their former partners. “They didn’t know what they had written, but they were moved when I later brought them a picture of them together with their notes,” she tells That’s via email.

One of her most memorable shoots was with a couple who had divorced two years prior but were still working together to support their daughter who was preparing for the gaokao.

Image via Gao Meilin

She recounts in a Sixth Tone article published in March, “When I arrived, they had just finished doing a couple’s wedding photos at the studio. I told them to leave the setting as it was, with a red cloth hanging in the background, and photographed them then and there.”

Gao tells us that she still believes in marriage and family. “Although people’s attitude towards divorce in China is changing all the time, [my parents’] generation is very special. Before them, the divorce rate was low in China, while the divorce rate of our generation is so high that it even needs laws to slow it down.”

On January 1, 2021, the Chinese government enforced a new law to deter couples from impulsively getting divorced: They would first have to wait 30 days. This ‘cooling period’ does not apply to lawsuits that involve domestic violence and has ‘worked’ in some instances.

Silvia informs us that one of her friends has delayed proceedings because of this law. Instead, they are choosing to quietly separate, settling into different homes and dividing assets themselves.

Data from the Wuhan Civil Affairs Bureau show that after a 30-day cooling-off period and a 30-day processing period, 58% of couples gave up registration after applying in March 2021.

In addition to the 30 days, both parties must agree to divorce and the application can be rejected if one party refuses. These new stipulations have been viewed as detrimental, especially for those in abusive relationships that are unreported.

An article published by South China Morning Post in May 2020 revealed that 20% of Chinese women in 2019 were deeply unhappy and regretted their marriage. Unequal division of housework is a big issue and one that is consistent across the world.

The article goes on to tell the story of Liu Fang, a married Shanghai woman in her 30s who reached a breaking point in her family and took to the internet to share her frustrations. “What I regret most in my life is getting married and having a kid. How wonderful to just be alone!” Liu posted on Weibo.

Expecting to enter a happy marriage, Liu says the amount of work tripled. As an employee at a financial data firm, she notes that the burden of office work, chores at home and childcare make divorce an appealing option.

Moving On

Divorce rates in China are also rising because of a gradually shifting attitude and increasing openness towards divorce in society, paired with low cost. Divorce is no longer seen as ‘谈虎色变’ (tan hu se bian), a Chinese idiom which means ‘scared at the mere mention of.’

The total number of divorces registered by the Civil Affairs Department has steadily gone up since 2007. However, the total number of registrations was 3.73 million in 2020, a 7.66% decrease from the previous year and even lower than the total in 2018, 3.8 million.

Image via Gao Meilin

Beijing-based relationship coach and therapist Li Wen has witnessed attitudes towards divorce change firsthand with her clients.

“In recent years, the status of Chinese women is changing. In the past, it was more difficult for women to leave an unhappy marriage because men were the breadwinners of the family. But as we see more women earn good money to support a family, they feel confident to take action and leave a marriage that isn’t fulfilling,” Li tells us on a call from the capital city.

Women make up 73.4% of the plaintiffs looking for a divorce, and the reasons often cited are irreconcilable differences (77.5%) and domestic violence (14.9%). The time frame in which divorces usually happen is between two to seven years after marriage.

China is one of the countries in the world where divorce is relatively free with simple procedures. In a mutual separation, a couple can head to their local marriage bureau to apply for a divorce for free.

In comparison, to apply for a divorce in the UK, it costs GBP550, and in Canada, it costs approximately CAD632 (including court fees). The new marriage law weakens the constraint of economic interests on marriage. In other words, the extent of property losses caused by divorce is greatly reduced, which further lowers the cost.

The lower the cost of divorce, the easier it is to give up the union, which makes people potentially less invested in the marriage. It seems people spend less time searching and making careful decisions before marriage. As a result, the husband and wife are often mismatched, which in turn leads to more divorces.

Beyond the marginal costs of leaving a spouse, Li points out that another key reason couples are divorcing is that they get married before they truly know each other.

“One of my clients mentioned that she only knew her partner for three months before they got married. She soon after learned that her spouse was irresponsible,” Li tells us. “Now she is pregnant and also considering a divorce.”

While Li notes that relationship counseling and therapy are quite expensive, she adds that simply reading self-help books can improve a relationship by better understanding how to communicate feelings.

But for some couples, divorce is a way to set a precedent. As Gao tells us, “My father later told me that my mother’s last words to him before the divorce were, “I wanted to set an example to my daughter that if she was unhappy in her marriage, she would have the courage to divorce.””

Whether we’ll see divorce become more commonly accepted in Chinese society remains to be seen. But it’s clear that more children today are growing up with divorced parents than ever before in China.

How this family dynamic will shape their future relationships will impact perceptions of both marriage and divorce.

With societal standards and notions of romance changing, coupled with the rise in women’s power – marriage, a social construct, no longer seems to serve the same purpose it once did.

On the other hand, marriage counselors and lawmakers aim to rebalance the scale by providing more education to the public on the true responsibilities of marriage.

If counseling and therapy become mainstream, it could help turn the tide for couples of future generations.

But for now, it’s clear that a growing number of people are disenchanted by marriage, which will have a significant impact on China – for better or worse.

Formidable Couples

Dr. Kong shared with us five suggestions that she believes can help couples better communicate and, ultimately, lead to a fruitful and happy marriage.

1. Accept professional counseling before marriage

Setting clear boundaries and expectations before a union is important. You are responsible for supporting and helping your partner and making both your lives happier and more successful. However, many people are not aware of this, they get married only hoping to get something from others. They may think you are my husband or wife, so you should do what I want you to do. There are also some sensitive topics such as money, sex and the relationship between parents that should be openly discussed in professional premarital counseling.

2. Set Rules

The second is to set some rules that both the husband and wife must obey as these irrefutable rules are a defense line to protect the marriage. There is a rule between my husband and me: no quarreling overnight, and at midnight, one of us must apologize and the other must accept it. There is also a fixed agreement between the two of us to set a time for us alone. We cannot quarrel in front of the child, and so on. We set rules and strictly obey them.

3. Learn to deal with conflicts

Each conflict is actually the best opportunity for us to understand ourselves and each other. We should learn to deal with the conflicts between husband and wife, and find out what are the unmet needs behind the emotions, and learn to communicate our emotions and needs. This kind of discussion will not lead to divorce, but a more intimate relationship.

4. Keep learning and improving

Marriage seems to be a matter of two people. However, only one is enough to determine the happiness in marriage. If you change, the other person will also change. Therefore, we suggest that both spouses or at least one of them should keep learning and improving, learning how to manage an intimate relationship, how to communicate, how to improve so that when problems occur, we can find solutions to problems during learning.

5. Find a professional marriage counselor

Leave professional matters to professional people. Many couples who came to me were in trouble and were about to divorce. After professional counseling, the problem was solved quickly. If your marriage has problems, it is still recommended to turn to a professional marriage counselor for resolution.

Additional reporting by Ryan Gandolfo and Joshua Cawthorpe

[Cover image via Gao Meilin]

Recent Comments